5 Fascinating Details That “Oppenheimer” Left Out

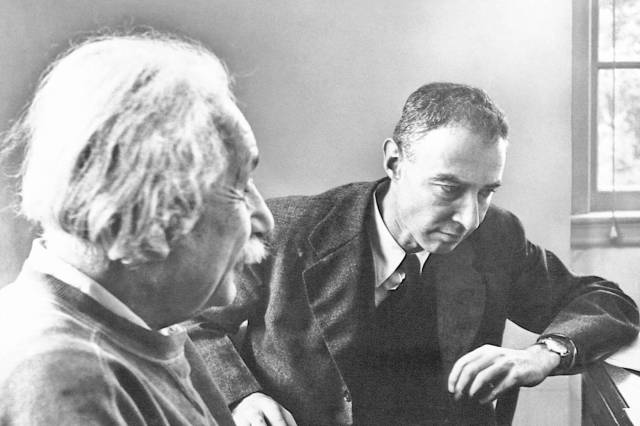

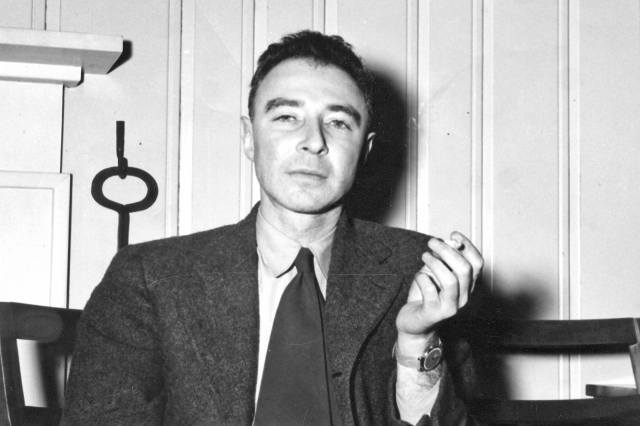

Oppenheimer was one of the most successful films of 2023, and with good reason. Christopher Nolan’s account of the “father of the atomic bomb” is a meticulous biopic and gripping thriller all at once, with its depiction of the Trinity nuclear test ranking among the most awe-inspiring visual spectacles in cinema history. After grossing an eye-popping $960 million at the box office as part of the “Barbenheimer” phenomenon, the movie dominated the 2024 Oscars, winning seven awards including for Best Picture, Best Director (Christopher Nolan), Best Actor (Cillian Murphy), and Best Supporting Actor (Robert Downey Jr.).

The film didn’t tell the whole historical story, however — no single movie could — and some of the details that were omitted are as compelling as the ones that made it into the final cut. Here are five of them.

The Nuclear Fallout From Los Alamos

Developing and testing nuclear weapons is a dangerous affair, especially for the people living downwind of the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico, where J. Robert Oppenheimer and his team conducted their top-secret research. “Some people thought it was the end of the world,” said Paul Pino of Carrizozo, New Mexico, located some 40 miles south of Los Alamos, in an interview with NPR after the film’s release. “They thought, the sun’s coming up on the wrong side of the world.” Oppenheimer portrays the testing site as essentially barren and desolate, which isn’t exactly accurate.

The Trinity test itself was conducted 200 miles from Los Alamos in the more remote Tularosa Basin, but even that region was hardly unpopulated: Half a million people lived within 150 miles of the explosion, many of them Indigenous and Hispanic peoples, and these “downwinders” have been called the world’s first victims of nuclear fallout. These groups have reported high rates of heart disease and cancer, not to mention their cattle’s hair getting burned off and their land being covered in white dust in the wake of the actual explosion. The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act was passed in 1990 to address some of these concerns, but many of those affected say its parameters are too narrow and they’ve been left in the cold.