Why Do Older Movies Look Faster?

When we think about old, silent films, we’re likely to picture the choppy, fast-paced movements of Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton, or perhaps the newsreel footage of Babe Ruth hitting a home run and seemingly zipping around the bases at 40 miles per hour. As talented as these individuals were, they weren’t capable of moving at speeds far beyond the range of normal people. So why do they appear that way on film?

Film Only Provides the Illusion of Movement

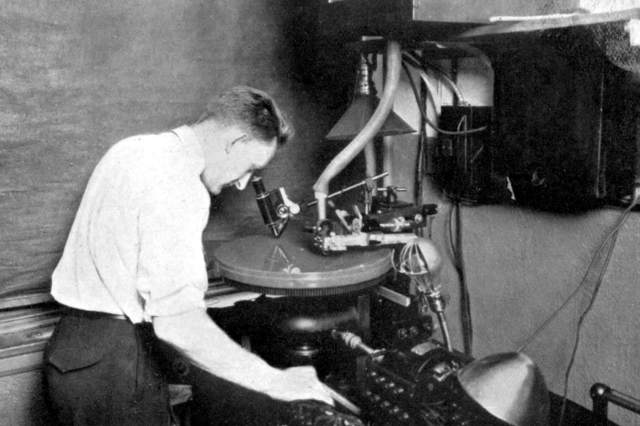

To answer this question, we need to go back to some of the basics of filmmaking. Throughout the history of cinema, movie cameras have never been able to faithfully capture real-life movement. Rather, they record a series of still images in rapid succession, and replay them at speeds fast enough to trick the human mind into perceiving movement.

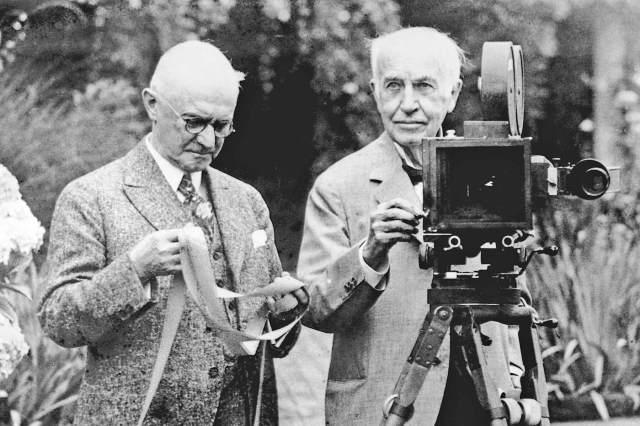

The number of individual images (or frames) displayed in one second of film is known as the frame rate, measured in frames per second (fps). Thomas Edison, who patented (but didn’t invent) the movie camera, noted that film needed to be shown at a speed of at least 46 fps to provide the illusion of movement. But in the early days of cinema, this proved too pricey to be practical, and some filmmakers found that the visual illusion could be sustained — and expensive celluloid film stock conserved — with frame rates closer to 16 fps, or even as low as 12 fps. While this speed was considered fast enough for a movie camera of that era, it is noticeably slower than the 24 fps rate that later became commonplace for both filming and projecting. And when old footage filmed at 16 fps or lower is accelerated for replaying at modern speeds, it will make the objects on screen move noticeably faster.