Does the Thumbs-Up Sign Come From Gladiator Fights?

The thumbs-up sign is one of the most instantly and universally recognized symbols of approval in modern Western culture. This ubiquitous gesture appears in everyday acknowledgments between friends and colleagues, in emojis across social media, and in numerous TV shows and movies, with famous fictional proponents including “The Fonz,” Borat, and Arnold Schwarzenegger’s T-800 in Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

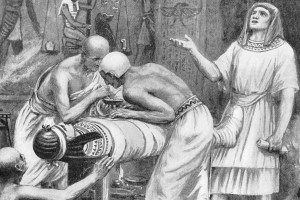

Despite this popularity, a fair amount of confusion and misinformation surrounds the origin of the thumbs-up sign. Most notably, many people believe the gesture has its origins in ancient Roman gladiator fights, where spectators supposedly used a thumbs-up to spare defeated fighters and a thumbs-down to condemn them to death. This narrative has been reinforced by popular culture — particularly the 2000 Academy Award-winning movie Gladiator. The historical reality, however, is not nearly as clear cut as Hollywood would have us believe.

The Problem With Pollice Verso

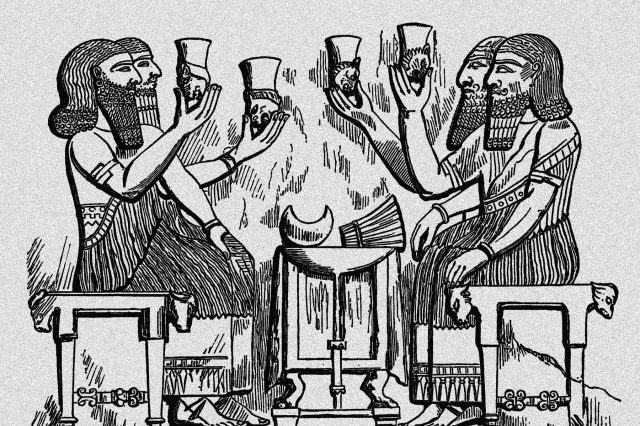

It’s true that there’s a link between thumb gestures and gladiator fights in ancient Rome, but we don’t know exactly how the gesture was used. At the heart of the historical debate is the Latin phrase pollice verso, meaning “with a turned thumb.” This phrase appears in ancient Roman literature, including in connection with gladiatorial contests, but its exact meaning remains unclear to historians. We don’t know whether pollice verso referred to a thumb being turned up, turned down, held horizontally, or concealed inside the hand to indicate positive or negative opinions — or, in the arena, to signal whether a gladiator was spared or killed.

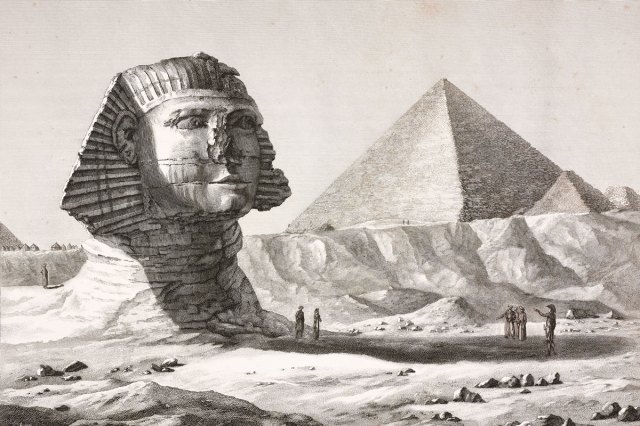

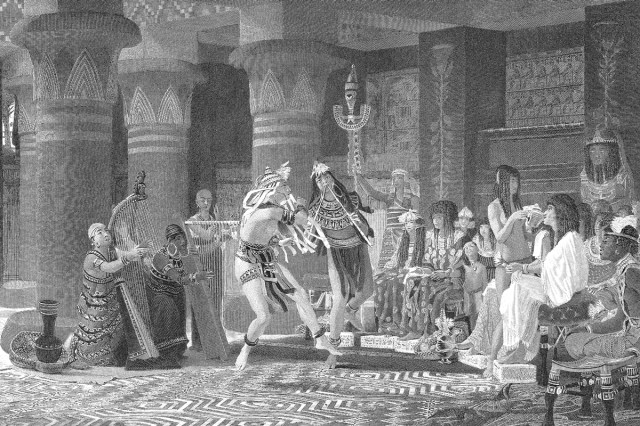

The ambiguity of ancient sources has allowed later interpreters to project their own meaning onto the gesture. The most significant example of this in the modern era is Jean-Léon Gérôme’s 1872 painting “Pollice Verso.” The painting brilliantly captures the power and drama of a gladiatorial contest, with one gladiator standing above his fallen opponent, who, lying stricken on the ground, raises two fingers to plead for mercy. In the stands of the Colosseum, Roman spectators, including an animated group of vestal virgins, signal death for the defeated gladiator with a thumbs-down gesture. The painting greatly popularized the idea that a thumbs-up signaled life, and a thumbs-down signaled death for a defeated gladiator.

It didn’t take long, however, for scholars to highlight the painting’s lack of a solid historical foundation in its portrayal of the gladiatorial contest. In 1879, a 26-page pamphlet titled Pollice Verso: To the Lovers of Truth in Classic Art, This Is Most Respectfully Addressed presented evidence against the historical accuracy of the thumb gestures in Gérôme’s painting.