5 Hidden Treasures That Actually Exist

It’s hard to surpass the romance and adventure embodied by hidden treasure. The allure of lost riches has lived with us throughout human history, and the interest in such fables has never wavered — hence the enduring popularity of fictional works such as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and, more recently, the Indiana Jones movies.

Unlike many legendary troves — such as Montezuma’s treasure, which has fired the imagination of treasure hunters for centuries, despite little evidence as to its actual existence — some hidden riches are known to be very real, but their whereabouts are now tantalizingly lost. Here are five of these lost treasures, all of which continue to inspire treasure hunters and historians alike in their ongoing quests for discovery and long-lost riches.

Lost Fabergé Imperial Eggs

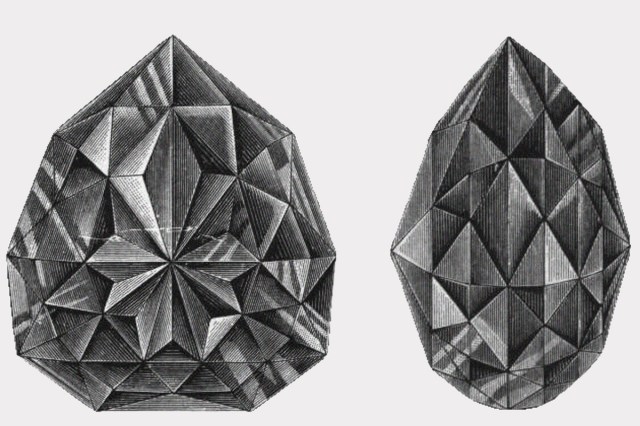

Few things in life are more jaw-droppingly lavish than Fabergé eggs, ornate decorations commissioned by Russian tsars and created by the jewelry company House of Fabergé between 1885 and 1917. The most well known and extravagant are the Imperial eggs, of which 50 were created but only 44 are known to have survived.

The most recent discovery came to light in 2011, when the long-lost Third Imperial Egg was accidentally discovered in an American flea market. It later sold for an undisclosed amount in 2014 after being valued at $33 million.

After the start of the Russian Revolution in 1917, the Bolsheviks ransacked and looted the imperial family’s palace and nationalized the House of Fabergé, and some of the Imperial eggs were lost. Researchers believe that as many as five Imperial eggs have been destroyed, but there’s still a chance that at least one Imperial egg is out there waiting to be found.