8 Military Honors Beyond the Purple Heart

The Purple Heart is the oldest and arguably most famous military award in the U.S. Its origins stretch back to 1782 and the Badge of Military Merit — a heart made of purple cloth — which became the modern Purple Heart in 1932. The medal is awarded to U.S. military service members who have been wounded or killed as a result of enemy action. In total, more than 1.8 million Purple Heart medals have been presented.

However, it’s far from the only military decoration in the U.S. In fact, the U.S. military maintains an extensive system of honors and awards. There are more than 100 decorations, including medals, service ribbons, ribbon devices, and specific badges, recognizing various forms of service, valor, achievement, and dedication. These acknowledge everything from the highest acts of heroism in combat to meritorious service in peacetime operations.

Let’s take a look at some of the most prestigious and notable U.S. military decorations. Each one, in its own way, recognizes the exceptional service and sacrifice displayed by members of the armed forces — and in some cases, civilians.

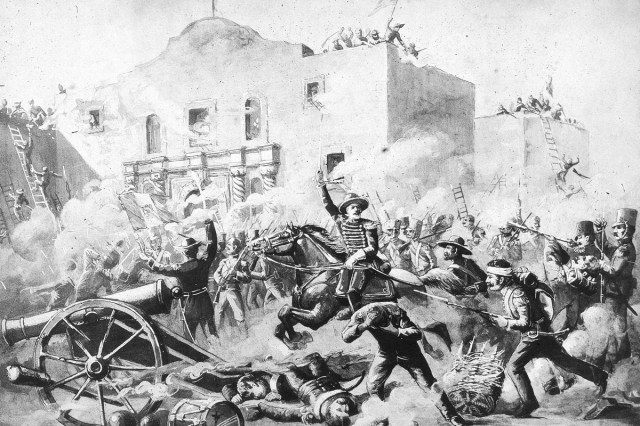

Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor is the highest medal for valor in combat that can be awarded to members of the U.S. armed forces. While the Purple Heart is awarded to U.S. military service members who have been wounded or killed as a result of enemy action, the Medal of Honor is for acts of extraordinary valor. Created in 1861, the medal recognizes the bravest of the brave. Since its inception, more than 3,500 service members have received the Medal of Honor. Only 19 have received it twice — five of those recipients were Marines with Army units who received both the Army and Navy versions of the medal, and 14 others received it for separate acts of supreme valor.

The recommendation process for receiving the Medal of Honor can be complex, taking more than 18 months as it passes up the chain of command. It’s ultimately approved or disapproved by the president of the United States, who personally awards the medal.